The Complete Short Stories

“What’s a poor reader to do but laugh?”

Samuel Langhorne Clemens, better known as Mark Twain, was once called “the most conspicuous person on the planet”—words he cherished.

At the time he certainly was. Twain knew America from shore to shore as circumstances and whims took him all over the country.

Wherever he was, his observations ran deeper than merely reporting local color. He dug in, discovered the nature of both place and people, and set about to share truths with humor and incredible insight. Twain was born in 1835 and died in 1910, both years when Halley’s Comet was visible, once remarking that both he and the comet were “nature’s unaccountable freaks.”

Twain did not know what he was going to be when he grew up. He explored vocations as a printer, a riverboat captain, a public speaker, finally capturing the American culture and spirit in his writing.

His early work celebrated turn of the century America’s exuberant youth and optimism with stories about mining and tales set on the grand, winding Mississippi River. Who knew so much happened on what might seem to others a plain, old, meandering body of water?

His worldwide popularity was based on his genius in nailing the spirit of America with a keen, sometimes biting, always on the mark sense of humor. Although his work became darker as he and America lost the lightness of youth with the First World War and later the Depression, he earned distinction in the literary canon as one of America’s greatest writers, with a twist of the iconic and enigmatic.

At times Twain drifted away from the easy and often lucky life he had created for himself; but when he got himself in trouble—not rare—back to writing he went, always landing on his feet—often to financial success. And at 70 years of age, Twain sailed to Europe to receive an honorary degree from Oxford University.

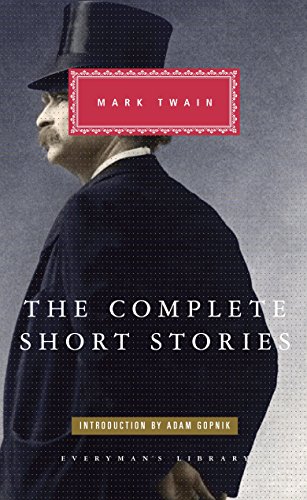

The Complete Short Stories is Everyman’s Library’s new deluxe edition of his short fiction. Superior production quality, including the quality of the paper and the red rich cover, makes this particular edition worthy of the classic tales within.

Mark Twain’s story are delightful to read and reread for many reasons: the twists, the literary trickery, exaggeration, satire, understatement, keen word choice, and uninhibited sense of the ridiculous—all resulting in an inadvertent suspension of disbelief on the part of the reader not unlike what is required with magical realism, ironically grounded in universal truths.

For in reading Twain, you get sucked in under the guise of entertainment residing in a kaleidoscopic vision of America’s personalities, regional quirks, and ever capricious national character—then sucker punched with an insight that knocks you to the ground.

For instance, in “My Watch,” he writes as himself in the first person voice about an inept jeweler who mishandles his watch. “But no; all this human cabbage could see was that the watch was slow. . . .”

As well, Twain, like Thurber, was highly alerted to sound. In his stories, bells toll, bees buzz, and birds make noises like cat fights.

In “What Stumped the Bluejays” the birds speak and express different feelings; they master speech that is not only complex, but “bristling with metaphor, too.”

With what could only be called genius, Twain captivates his readers with the miracle of Blue Jay speech, and then ends the brief tale with what later Americans would call a Shaggy Dog story: a let down, a sucker punch that tricks the unsuspecting reader.

This collection touches on several sub-genres, too. For instance, “Some Learned Fables for Good Old Boys and Girls: In Three Parts” stays true to fable conventions with such creatures as Dr. Bull Frog, Tumble-Bug, Professor Snail, Professor Angle-Word, et al, and also a moral. And although certain passages are reminiscent of Swift’s La Puta or Carroll’s “Jabberwocky,” Twain’s stories somehow ring absolutely original and characteristic of his humor. As in the following from the “Fables,”

“The fact that it is not diaphanous convinces me that it is a dense vapor formed by the calorification of ascending moisture dephlogisticated by refraction. A few endiometrical experiments would confirm this, but it is not necessary. The thing is obvious.”

Consider this from “A Medieval Romance:”

“The remainder of this thrilling and eventful story will NOT be found in this or in any other publication, either now or at any future time.” Twain concludes: “I will wash my hands of the whole business, and leave that person (the hero or heroine) to get out the best way that offers—or else stay there.”

What’s a poor reader to do but laugh?