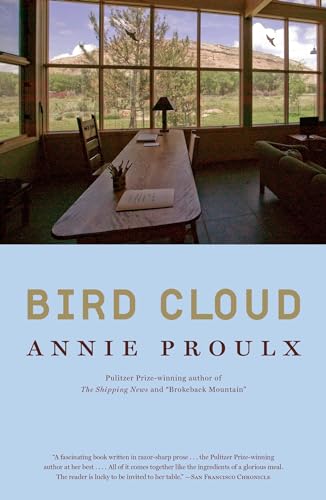

Bird Cloud: A Memoir of Place

Bird Cloud, Annie Proulx’s memoir-cum-construction diary is an amuse-bouche of a book, a lovely nibble of a thing, that has, strangely, been inserted somewhere deep in the rich, dense feast that is her life’s work, and not presented at the beginning, where such trifles belong.

From beginning to end, the reader never quite knows what to think of Bird Cloud. Nor does the reader know what kind of book it is or was meant to be. At times it is Mr. Blanding Builds His Dream House Way Out West. At other times, it is a memory piece in which the author listens for the echoes of other places, other times. And at still other moments it is a birdwatcher’s handbook, an ecological tract or, worst of all, a long, long infomercial for Polygal Windows, the Window of Choice at Bird Cloud!

And yet, here it is, this book, likely the closest thing to a memoir that we shall get from the famously prickly Ms. Proulx, author of perhaps the best novel of this generation, The Shipping News, and creator of the now iconic Brokeback Mountain. Which gives the reader a sense of anticipation upon opening Bird Cloud.

In it, Ms. Proulx prowls about Wyoming, in the area of Centennial, looking for a home. She sees a sprawling piece of land—a sheer cliff, an island, a river all embedded within—spots a cloud in the shape of a bird up above, and buys it, names it, and, ultimately builds what should have been but never will be her dream house on the site—perhaps because the site itself is aboriginal enough to exist in something like Dreamtime, a state jutting away from our own reality. Bird Cloud is a place of winds that scour clean, that are merciless and relentless, that blow birds across the sky, as Proulx notes, like cannonballs from a cannon.

Early on, in a moment of self-revelation, Ms. Proulx comments: “Well do I know my character negatives—bossy, impatient, reclusively shy, short-tempered, single-minded. The good parts are harder for me to see, but I suppose a fair dose of sympathy and even compassion is there, a by-product of the writer’s imagination. I can and do put myself in other’s shoes constantly. Observational skills, quick decisions (not a few bad ones), and a tendency to overreach, to stretch comprehension and try difficult things are part of who I am.”

True enough, from what the reader gleans from the text. Especially the tendency to “try difficult things” part.

But she leaves so much more out: her acceptance, even celebration of what is, flaws and all, over what might have been, or her outrageous Romanticism of the old-school kind—think Keats and Coleridge—wed as deeply to Nature as those British poets were, but to a bolder and uglier nature of crags and sagebrush and bald eagles, of the wild tides of Newfoundland and the evergreen majesty of the Medicine Bow mountains, all without a dancing daffodil in sight. Also missing from her list are her terrier mind and eagle eye, a combination of animal traits that lends the best of her fiction the authenticity of detail and this book the dogged determination to see the damned thing through (like Bird Cloud itself) even after the fizz of the original compelling idea had fallen flat.

In other words, she omits her own flint. As well as the fact that, a New Englander by birth and upbringing, like other staunch women (Katharine Hepburn, Barbara Bush and even Big Edie Bouvier—all come to mind), she brings New England with her now wherever she goes. And that attribute, the sheer Nor’easter in her soul, is so important to understanding the woman and her work.

In her long and distinguished career, Ms. Proulx has won a Pulitzer Prize, a National Book Award, the Irish Times International Fiction Prize and a PEN/Faulkner Award. And, sadly, Bird Cloud is a book that, had you or I written it and wished to see it published, we had better have won all those prizes as well in order to see it in print.

Bird Cloud is an oddity, a brief moment in idle in an otherwise ever-revving career. What came before and what likely will come after will leave the reader fully indulged, educated, enlightened, and delighted. What sits within the covers of this slim volume, however, leaves the reader disgruntled. Like the house itself—and literary history is filled with these houses, from Manderley to Brideshead, that soak up so many of our hopes and dreams and give so little back—that which was meant to be the dream house, the final and ultimate home, complete with Japanese soaking tub, that turns out to be unlivable in the winter months due to isolation and wind shear and mounting snow—Bird Cloud also turns out to be without life, a thing to admire, but, ultimately, something to scrawl firmly onto the list of Ms. Proulx’s quick decisions and overreaches.

This is not to say that there is not beauty here. Again, Ms. Proulx parallels the nature of the land within the contents of her book. Both have a lonely beauty—this prose and the rough land that inspired it. Both are places of heavy gravity. And both have a beauty that, when spotted, leaves the viewer quite breathless.

Like this. Like this moment of description in which she tells us about the quick decision to build her house, and so much more about herself:

“The river at sunset became a mottled green and peach in patterns that recalled the marbled end pages of old books. Quickly the evening dusk filled with darting swallows, their dark bodies gradually absorbed by the intensifying gloom. The great horned owl called from the island and everything fell silent except the murmuring river and a more distant owl. In this place there was so much to know. I told myself the house had to be built. I began to think of it then as a kind of wooden poem.”

When one can write a passage like that, one gets to write whatever else one pleases. . . .